Written contributions and essays by Tony Heaton

Click on the image to read interview....

Museum Collections on Prescription: Health, Wellbeing and Inclusivity, online series April 2021

A SUBJECT SPECIALIST NETWORKS SERIES

15, 22 AND 29 APRIL 2021, 15:00–17:00 (BST)

We were delighted to collaborate with two other professional networks on this series, the British Art Network, and the European Paintings pre-1900 network. Over three online sessions, we explored the topic of health, wellbeing and inclusivity in the context of arts and heritage collections with a range of arts and healthcare professionals.

All sessions were supported by live captioning and British Sign Language interpretation. Recordings online very soon.

Download the series resource pack here (PDF): Further reading and refs for ‘Museum Collections on Prescription’ series

Nothing about us without us – disability, inclusivity and engagement. 15 April 2021, 15:00–17:00

Convened by Tony Heaton, Sculptor and Disability Activist

This session explores the intersection between collections, disability and wellbeing. Are disabled makers and visitors reflected in public collections and their programming? Do they have a voice at the table? Are sector professionals responsive to the wellbeing of disabled visitors? Tony Heaton speaks to museum professionals and artists in the first of three online sessions which consider the potential for museum/heritage collections to support and enhance visitor wellbeing.

Attendee downloads for this session (PDF):

Convenor and contributors’ bios for ‘Nothing about us without us’ session T Heaton 15 April 2021

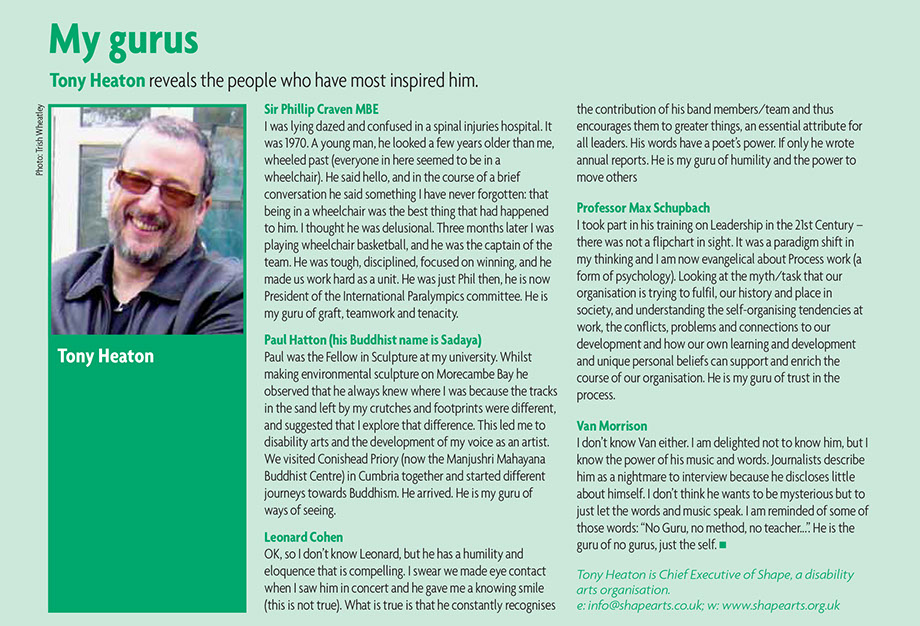

Tony Heaton © Rachel Cherry

Tony Heaton OBE is a practising Sculptor, Chair of Shape Arts and Consultant/Advisor to many major cultural organisations, including: The British Council, Tate and the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries. He is the initiator of NDACA – the National Disability Arts Collection and Archive. His sculpture, Gold Lamé, recently occupied The Liverpool Plinth and is currently installed at the Riverside Museum, Glasgow. His Monument to the Unintended Performer was installed on the Big 4 at the entrance to Channel 4 TV Centre in celebration of the 2012 Paralympics. His sculpture Squarinthecircle? is situated outside the school of architecture, Portsmouth University. He was awarded an OBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours 2013 for services to the arts and the disability arts movement and has an Alumni Award from Lancaster University and honorary Doctorates from both the University of Leicester and the new University Bucks.

Taking part in this session:

Sonia Boué, artist www.soniaboue.co.uk

Paulette Brien, Curator, Grundy Art Gallery

Alex Cowan, Archivist, Shape Arts

David Hevey, CEO of Shape Arts

Aidan Moesby, artist www.aidanmoesby.co.uk

Zoe Partington, visual artist and creative consultant www.zoepartington.co.uk

Tanya Raabe-Webber, artist www.tanyaraabewebber.wordpress.com

Christopher Samuel, artist www.christophersamuel.co.uk

Prof Richard Sandell, Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, University of Leicester

Aminder Virdee, artist www.aminder-virdee.com

Watch this session here:

Jennifer Lauren Gallery

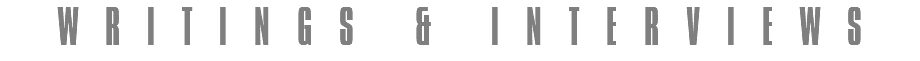

Tony Heaton interviewed on Thursday 17th December 2020

The talk was carried out at 6.00pm for one hour on zoom. You can find the video of the talk below with BSL interpretation.

You can read a transcript in PDF format HERE

Access Fylde Coast

Tony Heaton introduces NDACA at the Grundy Art Gallery Blackpool.

The National Disability Arts Collection and Archive exhibition tells the heritage story of a group of disabled people and their allies who broke down barriers, helped change the law and made great art and culture about those struggles. Including artworks, documentary materials and ephemera, the exhibition will have a particular focus on artists based in the North, and will examine the impact of their work at both a local and national level.

What if Everyone Was Disabled…? BBC Radio 4

Seriously….

The writer, actor and rights activist Mat Fraser imagines how different our world would be – in design, technology and attitudes if everyone was disabled.

Contributions from:

Tony Heaton, Liz Carr, Jane Simpson, Julie Fleck, Samanta Bullock, Liz Sayce

Producer: Steve Urquhart

First broadcast on Thursday 16th July 2020 Listen here

Outsiders BBC Radio 4

Can anyone declare themselves an artist? David considers the so-called rules as he wonders how open the established art world is to outsiders. He leads an uncompromising - and at times uncomfortable - discussion about activism, criticism, exploitation, entitlement, preconception and power.

Contributors include:

Liv Wynter, artist, activist and writer

Matt Peacock, artistic director, Streetwise Opera

Tony Heaton, artist, sculptor and chair of Shape Arts

The White Pube (Gabrielle de la Puente and Zarina Muhammad), critics and curators

Sir Nicholas Serota, chair of Arts Council England

Broadcast 1.30pm on Sunday 9th September 2018 Listen here

A Seamless Transition

Tony Heaton OBE, formally CEO of Shape Arts, now focusing fully on his long-established career as an artist, and Chair of the Shape Arts Board, talks about the challenges of managing a change of Chair and CEO in this case study on the theme of ‘leadership through governance’. Tony also writes about his own leadership story and style.

Read the full case study here

Tony Heaton:

Art out of protest

As Tony Heaton resurrects some crip humour with his latest sculpture 'Raspberry Ripple' commissioned by Lumiere London, Allan Sutherland talks to the artist about his career.

See the interview HERE

Tony Heaton – Activism Through Art

Apr 02, 2017 10:00 pm | Martyn Sibley

Buckle up guys. Episode 3 with Tony Heaton is a long one. The stories told by the CEO of Shape Arts were too good to cut them short. Plus Tony’s lust for life shines the whole way through our interview.

I first met Tony when I was looking to leave Scope after 5 years there. A job was going at Shape Arts for their marketing manager. In my late 20’s it was a big jump, with lots of responsibility. Unfortunately I didn’t get the job, but Tony had wanted to give me the role. So much so he wrote a handwritten letter of encouragement for my future.

A true gentleman.

Over the years Tony has managed music bands, studied at art school, fought for disability rights, and managed high impact organisations. His biggest claim to fame is being commissioned for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games to create a sculpture. Not to forget his Queens honour too.

In this episode you’ll hear how he found art as a tool for activism, why changing your life every 10 years is healthy, and general thoughts on the disability movement.

As always, please follow/rate the podcast, share it on social media, and let me know your thoughts on new guests.

Listen to Tony and I chew the fat here.

See you next time!

Martyn

The Incorrigibles: Perspectives on Disability Visual Arts in the 20th and 21st Centuries:

Tony Heaton contribution entitled -

Different Shoes

A quote from the travel writer Bill Bryson1 might be a strange place to begin an essay that sketches out something of the history of

Disability Arts, but bear with me.

Bryson introduces us to a study of national inventiveness produced by Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry, which concluded that in the modern era, Britain has produced 55 per cent of all the world’s ‘significant inventions’, against 22 per cent for America and 6 per cent for Japan. This is an astonishing proportion and amongst this

innovation we must count Disability Arts. It is a genre conceived in the UK, is inextricably linked to the Disability Rights movement and it

grew out of a time when Disabled people in the UK were questioning the perceived view that disability was an issue for the medical, health

and social services, rather than a human rights issue and therefore something we could all of us address in removing barriers and

challenging prejudice and discrimination.

It is difficult to pin down the actual birth of this term ‘Disability Arts’ and its context but as Shape2 celebrates its 40th anniversary this

year, 2016, it is probably reasonable to consider that it was around the mid-1970s.

The National Disability Arts Collection and Archive3 (NDACA), a project led by Shape and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, in embryo for some years and launched coincidently this year, will doubtless unearth

some documentary evidence that may shed light on the birth of Disability Arts, or some long forgotten event where this term was

coined, but let’s not worry about it.

Disability Art exists and I for one feel better and stronger in knowing this.

The politicisation of disability and the radical nature of much of the art of that historical time fused together and this, coupled with the Social Model of Disability proposed by Mike Oliver and Vic Finkelstein, was potent and liberating for many Disabled people.

A vanguard fought to force changes; to the built environment, goods and services and discriminatory attitudes to Disabled people and this change started to happen. It challenged local authorities and hegemony and built positive relationships with allies who

recognised that we quite rightly wanted civil rights and who supported this struggle to legislation. This of course meant demanding access to art galleries, museums and theatres and by that we meant access through the front door.

Many Disabled artists have told me that whilst at art college they were dissuaded from looking at issues relating to their impairment or their Disability identity, that this was not something

worth developing as part of their practice if they wanted a successful career. This is a form of oppression and one that I was fortunate not

to face; on the contrary, the Fellow in Sculpture at my university observed that my footprints in the sand were different from the rest of the students and that this might be something to investigate as part of my practice. I did – and started making my own disability artwork back then in the 1980s. I just didn’t realise at that

time that there was something called ‘Disability Arts’ and that it was just beginning to happen.

I exhibited my work and was approached by North West Shape who provided me with opportunities and a network. Coincidently at

this time, 1986, the London Disability Arts Forum (LDAF) was founded and Disability Arts in London (DAiL) magazine was established to

highlight, promote and review the work of organisations such as Shape, Graeae4 and Heart n Soul5, including the creative work of

individual Disabled people.

I met and exhibited with others from what might be termed the first wave of Disabled visual artists in an LDAF promoted show at the

Diorama Gallery, London, called ‘Out of Ourselves’: with Nancy Willis, Trevor Landell, Lucy Jones, who are all still creating work, and Adam Reynolds.

Adam was an exceptional sculptor who worked in a range of materials including scrap, lead, copper and found objects, chosen deliberately to confront the viewer to reconsider the value and beauty of materials rejected and over looked. This he described as being: ‘founded on my lifelong experience of disability and to challenge the commonplace assumption that this renders life all but useless

and without value’.

He made figurative and abstract works, a number of which are in the Shape Arts Collection. (Adam was both a trustee and Chair of Shape). Adam stated: ‘I am clear that my greatest strengths stem from the fact of being born with muscular dystrophy, apparently my

greatest weakness’.

Adam died in 2005. His obituary was written for the Guardian by Tate Director Sir Nicholas Serota and Shape perpetuates his memory

through the Adam Reynolds Memorial Bursary (ARMB), an annual bursary aimed at a midcareer Disabled artists.

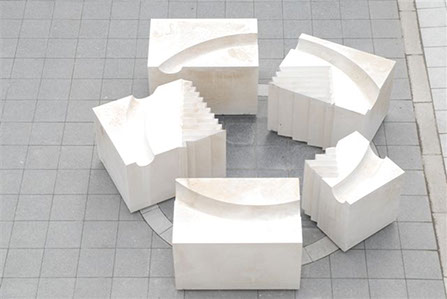

Left: Tony Heaton, Monument to the Unintended Performer,

steel, neon, (gold, silver, bronze lacquer), 15.24m, 2012

Paralympic Games, installation on the BIG 4 outside Channel 4

TV Broadcasting Head Office, London. Technical support

FreeState.

Photograph Dave King

To date the artists Noëmi Lakmaier, Sally Booth, Caroline Cardus, Aaron Williamson, Aaron McPeake, Simon Raven, Carmen

Papalia and Çağlar Kimyoncu have undertaken the ARMB in some of the UK’s most creative contemporary galleries: the Camden Arts

Centre, The Bluecoat Gallery, the BALTIC, Spike Island, the V&A and the New Art Gallery, Walsall. The sculptor Sir Antony Gormley

described the ARMB as the most practical and powerful way to continue doing what Adam did to make the possible palpable.

By 1990 there was a proliferation of organisations throughout the UK and Northern Ireland with events and happenings across all art forms. This continued throughout the 1990’s, with Disability Arts forums and consortiums and the development of 16 organisations such as DASH in Shropshire and DaDaFest6 in Liverpool.

The internationally renowned artist Yinka Shonibare MBE said: ‘My career in the arts started in 1992 with Shape. When I left Goldsmiths College I was looking for opportunities to develop my career. Shape

offered me my first opportunity to be involved in the arts. What Shape does for Disabled artists can make a very big impact on their

development. It was certainly the case for me.’

Now, twenty five years later, this is still happening and the opportunities are greater and the networks are wider – regionally,

nationally and internationally. Back then much of this activity and development was reported through the pages of DAiL Magazine7 or DAM Magazine8: without both these publications, much of the history of Disability Arts would be lost. Editors Sian Vasey, Elspeth Morrison, Kit Wells and Colin Hambrook became the guardians and Colin Hambrook went on to launch the digital journal DAO9 (Disability Arts

Online) in 2002 and has been for over twenty years at the forefront of the commentary on Disability Arts.

Also in 2002 the Faith House Gallery was constructed at Holton Lee in Dorset10 where I was Director. This award-winning building was the first fully accessible gallery space dedicated to showing and promoting the work of Disabled artists. This was closely followed by a suite of artists’ studios and many of the artists from this first wave had work exhibited and many new Disabled artists had opportunities, often for the first time, to show work. The gallery was opened with a performance from Signdance Collective – Julie

McNamara, Allan Sutherland, Adam Reynolds, Aidan Shingler, Tanya Raabe-Webber, Rachel Gadsden, Sally Booth, Sue Austin and many

more artists performed, exhibited or made work there.

These artists continue to inspire and attract new waves of artists and allies who see the value, the truly unique stories and who want to

support and promote our work. Currently Shape and Artsadmin11 are delivery partners for Unlimited12, Unlimited International and Unlimited Impact, funded by the Arts Council, Creative Scotland, the Spirit of 2012 and Arts Council Wales. Initiatives such as these ensure that Disability Arts and work by Disabled artists will be seen by wider

audiences than those who pioneered the genre; this is inevitable, and some of the artists from those earlier times continue to develop

work through Unlimited including Aaron Williamson, Katherine

Araniello, Bobby Baker and Kaite O’Reilly.

The widely held definition of Disability Arts is: Art made by Disabled artists that is informed by or reflects the personal experience of disability.

It is not an aberration or a phase; it is not an apprenticeship into the mainstream (whatever that is). It is not a ghetto; it is a genre rich with the most audacious, moving, funny, thought provoking,

subversive, life-changing work. That this is so is witnessed by the fact that many of those, then, young artists, writers, performers and creatives are still today making work and making trouble, challenging injustice, prejudice and disablism.

Their histories and past trailblazing can be seen in the Chronology of Disability Arts13, created by the poet, writer and disability

historian Allan Sutherland who was commissioned in the early days of the visioning for NDACA to provide a tool to understanding how this disability culture came about.

Disability Arts has been described as the last ‘avant-garde’ and remains so.

In a world where much contemporary art is dull and conventional, conservative and dead, we should celebrate the existence of

Disability Arts.

That curators and critics fail to see beyond the phenomena of difference or disability – by that I mean impairment – means they obsess with the idea of the overcoming of our impairments. When they have written about that, they then struggle to say anything meaningful about the work we do because they come from such a

different place that they are often unable to appropriate the work, having neither the experience nor vocabulary to discuss it. This

deficit is an issue and crucial because we really do need many more Disabled people as curators and critics to help us to develop and

evaluate the work.

Perhaps the fact that Disability Arts is not valued is because Disabled people are not valued; but Disabled people will always be present in society, both as intended and unintended performers and artists. They will always explore themselves, their experience, how they see the world and how the world sees them. Artists who are, or who become Disabled will indubitably do this and make creative work as a result, thus perpetuating this world we call Disability Arts.

It is inevitable and it’s spreading out across the world, you can’t stop it.

1 Bill Bryson, The Road to Little Dribbling, Penguin Random

House UK, 2015 p195

2 www.shapearts.org.uk

3 www.ndaca.org.uk

4 www.graeae.org

5 www.heartnsoul.co.uk

6 www.dadafest.co.uk

7 www.ndaca.org.uk/NDACA-Dail

8 www.digital-disability.com/heritage/publications/damdisability-

arts-magazine

9 www.disabilityartsonline.org.uk

10 www.holtonlee.org

11 www.artsadmin.co.uk

12 www.weareunlimited.org.uk

13 www.disabilityartsonline.org.uk/Chronology_of_Disability_Arts

right:

Great Britain from a Wheelchair, Tony Heaton, wheelchair

components from two condemned ex-ministry wheelchairs,165cm, 1994.

Photographer: Paul Kenny

The Incorrigibles: Perspectives on Disability Visual Arts in the 20th and 21st Centuries

The drive to produce this book grew out of issues raised within two of DASH's recent projects:

1: Awkward Bastards took place in March 2015, the first in a series of conferences bringing together an array of speakers – including historians, curators and artists – to discuss a wide range of 'diversity' issues.

One recurring theme within the conference was around the decision, both historically and now, to self-identify (or not) as a 'Disabled' or 'black' or 'queer' artist. The positive and negative implications of doing so, and what these implications still tell us about the machinations and prejudices of mainstream cultural organisations, remains an ongoing important political debate as well as a deeply personal dilemma for artists.

2: Cultivate is a bespoke mentoring project for up and coming Disabled visual artists. As mentors within the project we became acutely aware that new and emerging Disabled artists were often unaware of the history and current context for potentially aligning their practice, aspirations and identity as artists within a wider 'Disability Arts movement'. They were also often unaware of the work and range of current Disability Arts organisations and the support and resources available to them through these channels.

We hope that this book provides the reader – Disabled or non-disabled, arts professional or generalist, community or social care worker or disability activist – with greater insight and confidence to engage with these issues, and that new dialogues will emerge as a result. The stories and artwork in this book unite the artists and demonstrate the strong vibrant genre that is progressive and inspirational to an emerging Disability Arts landscape. We are indebted to all the artists who responded with such openness, honesty and generosity of spirit.

This book is not just about Disability Arts and culture, it is a book about artists being artists, it is about a celebration of difference, it is about the will to survive as artists, it is about humanity, it is about the fact that art unites us all as human beings and that Disability Art is here and now!

We hope that The Incorrigibles will provide a valuable contribution at this significant and fundamental point in the history of Disability Art

and culture. Recognising and understanding the history of Disabled artists in the past and their position in the present will be the basis of generating new and more enlightened practices in the future.

this is tomorrow

this is live :

Shape Arts - Artist Talk:

Yinka Shonibare MBE on becoming an Artist

Broadcast Live, 10 February 2016

Guest Projects, 18.30pm - 20.30pm GMT

Yinka Shonibare MBE will be in conversation with Tony Heaton OBE, CEO of Shape Arts,

to discuss his journey as an artist.

Access

Tony Heaton

Access, or lack of it, is still the fundamental issue preventing disabled people from fully taking part in society in the UK, yet we are still – over forty years after legislation began to be introduced to begin to address this – creating buildings and transport systems that perpetuate discrimination. We have moved slowly since the late Alf Morris managed to get the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act 1970 passed by Parliament. This was the first legislation in the world to make it unlawful to discriminate on the grounds of disability; it was a landmark victory and a paradigm shift for many (Campbell and Oliver 1996).

‘Can disabled people go where you go?’ was the slogan of the Silver Jubilee Committee on access for disabled people back in 1977. It could just as easily have been the slogan for the recent Diamond Jubilee in 2012, because there are still many subtle ‘no go’ areas. Back then, local authorities started to look at the services they provided, realising that in many cases their approach to disabled people would need to move from ‘care and control’ to ‘choices and rights’. This was becoming evident from the burgeoning disability rights movement, ignited by the social model of disability (Oliver and Barnes 2012).More enlightened local authorities introduced codes of good practice building on the requirements of the Act. Access Groups wereset up, driven by disabled people who challenged local authorities about lack of access provision and who, as a result, began working with planning departments to fight for local solutions. This direct action resulted in positive changes as politicised disabled people ‘policed’ local developments.

Living as a disabled person throughout this time and being active in the war of attrition that has taken place between disabled people, governments, local authorities and institutions has given me certain insights. We have had allies in both government and some authorities, but our battles have been hard won against the many who simply do not care enough about access to simply think about how they, as people with power, might facilitate change.

Architecture and design are two great unseen social drivers that have

a profound effect on access for disabled people, but there is very little time spent in considering this within the teaching institutions – it is simply not on the curriculum (Hemingway 2011; Morris 1993). The building regulations demand minimum requirements to be in place, but many think these requirements are best practice when actually they are a bare minimum. Part M of the Building Regulations 1985, updated in 2004, now states that the requirements of the new part M no longer refer to ‘Disabled People’ – the aim of the new part M being to foster a more inclusive approach to design to accommodate the needs of all people.

Similarly, the explanation of the relationship between part M and the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 has been amended in ‘use of guidance’ to reflect regulations made or revoked. Interestingly, the guidance states that:

There may be alternative ways of achieving compliance within the requirements. Thus there is no obligation to adopt any particular solution contained in an approved document if you prefer to meet the relevant requirement in some other way.

(Planningportal.govuk 2008)

Colin Cameron: Disability Studies - a Student’s Guide

1

This unlocked architects and designers from the rigid and often lazy way access solutions were imposed, frequently reflecting a

medicalised approach – for example, the ludicrous situation of sumptuously designed toilet facilities in keeping with the general

design ethic of a building but with the accessible toilet looking like something out of a hospital. Nevertheless it seems that few

architects or designers exercise this freedom to seek more aesthetic solutions. It could be argued this is because they never even think

to consult disabled people as potential users of the public spaces they are creating. This is another example of the professional assuming they have all the answers or relying on theoretical solutions rather than lived experience.

In the 1980s, when local authorities were developing their codes of good practice, the Disabled Persons (Services, Consultation and Representation) Act 1986 required them to start seeking input from disabled people (Barnes 1996). I recall developing a county-

wide mobility handbook under the leadership of the county surveyor

and being told that I was considered to be an idealist and dreamer to imagine that wheelchair users in the future would be able to travel by bus. This was considered unthinkable and unachievable, yet twenty-five years later, that is exactly what I am doing – all it took was a change in design, a simple requirement. It is both shocking and amazing that it took so long.

Ironically, however, as I sit in my space on the bus, as decreed by law, should another wheelchair user at the next stop want to get on they will be denied because there is usually only space for one wheelchair user, even if the rest of the bus is empty. So both a partial victory and a validation on dreaming.

My earliest journeys on the train were taken in the goods van, locked in without access to any facilities and paying for the

privilege. This has slowly changed, but again space is limited and it is unlikely that two wheelchair users could travel together.

Having to request that passengers remove their luggage from the wheelchair space and waiting in hope that a staff member with a portable ramp will appear to get a wheelchair user off a train once all the ambulant travellers have alighted is partial, rather

than full access.

Theatres and cinemas provide limited access. Wheelchair users are segregated into specific areas while British Sign Language (BSL), subtitled and ‘relaxed’ performances are few and far

between. Booking concert and travel tickets may have been revolutionised via online booking systems, but if you want the accessible seats or spaces then you are forced to go through to an access phone line which will almost inevitably have limited opening hours and have the cost of the call attached: again, partial access. Or, you are provided with a wheelchair space but your non-disabled companion cannot sit with you due to spurious health and safety rules consigning all the ‘wheelchairs’ to sit in a ghetto with companions in a seated area elsewhere.

Recently when talking to architectural students I asked where they would go to seek access advice. They suggested doctors, physiotherapists, social workers. No one proposed consulting with disabled people, even though one was leading the discussion and seminar!

In conclusion it could be argued that we are achieving partial access, but is this potentially more disempowering? As it hints at the possibility of inclusion but the frustrating reality for many still remains tantalisingly out of reach and an unsatisfactory concession, it seems that, as a nation, we are prepared to accept a tokenistic solution. It may be thought that due to legislation the job is done, but it isn’t, and we are in a dangerous position in thinking everything is in place to ensure disabled people have an equal opportunity to take part in society. This simply is not the case. These partial victories need consolidating before they become lost.

Lois Keiden: Access all Areas Live Art and Disability

Access all Areas from

Wheelchair Entrance to

Squarinthecircle?

Tony Heaton

Looking back over my work I was reminded that much of it is actually concerned with the notion of access.

I then decided to take the Access All Areas audience on two journeys, one real, the second a journey in time between two pieces of work, a 'coming of age' of a sort, because the first piece Wheelchair Entrance was created 21 or so years ago.

Time-travelling back to 1989-90 required a jogging of memories: Thatcher was in power (no change there then), Nelson Mandela was set free after 28 years in prison, the Poll Tax was introduced, resulting in mass protest across the country (what happened to mass protest against injustice?), prisoners took to the roofs of Strangeways Prison in Manchester and controlled the jail for 25 days, the Berlin Wall was demolished and Germany was reunified.

The average price of a house was £71,000 — it's currently £250,000; and inflation was at 7.8%, now 4%.

Keith Haring died, Theo Adams was born. Van Gogh's portrait of Doctor Gachet was sold for a record $82.5 million, giving hope to all disabled artists that even though we are not valued in our own lifetimes, many non-disabled people will capitalise from us when we are gone; no change there either.

And I made Wheelchair Entrance.

Wheelchair Entrance, Tony Heaton

I attempted to exhibit this sculpture/assemblage in two shows that I had been offered, but both galleries refused to exhibit it, saying it was too dangerous. Now, I'm all for art that's dangerous, but they argued that 'people' could be hurt by it and it was in breach of health and safety. I argued that no wheelchair users, people of restricted growth or children would be hurt by it and that perhaps adults could just take responsibility for themselves, even visually impaired ones. Nevertheless, the work's intention was to be mildly inconvenient and

to get people to reflect on the fact that most places were totally inaccessible to wheelchair users in those days — don't forget, the Disability Discrimination Act didn't become law until 1995, some five or six years later, and we disabled people were beginning to protest at the injustice and discrimination we faced.

Squarinthecircle?, Tony Heaton (photo: Chris Smart)

The sculpture, or perhaps you might call it a public intervention now, didn't see the light of day again until the Access All Areas weekend.

This short journey through time brings me to the last public sculpture I've made, which is situated outside the School of Architecture at Portsmouth University. This piece is called Squarinthecircle? and consists of five separate blocks of Portland stone, weighing in total around eleven tons and occupying a space of about 20 feet in diameter.

This piece is also about access and power.

The sculpture brings together a number of aspects that have become intrinsic to my work: simple archetype geometry that reoccurs; the circle, symbol of perfection and eternity — Jung described it as the symbol of the self — the square, associated with stability.

When juxtaposed, the circle and square are considered to symbolise oneness, the elimination of imperfections and impairments. The mathematical challenge attempted by alchemists to try to square a circle was proved to be an impossibility.

The work consolidates these elements in an attempt to describe wholeness by bringing together the five individual blocks and uniting them in the geometry.

Due to the nature and juxtaposition of the work, the power at the centre is rendered inaccessible to many, particularly wheelchair users. So, again it becomes something that non-disabled people, non-wheelchair users can get through by negotiating the tight spaces between the blocks, but the centre is denied to wheelchair users, to whom it is inaccessible. Thankfully, this time there are no howls of protest that the work is in breach of health and safety, or that people might hurt themselves in this public sculpture or intervention.

Nevertheless, 21 years later, what has changed? We are still debating 'Access all Areas'.

This text is a reworking by Tony Heaton of his presentation as part of the 'Pull Yourself Together' panel.

Creative Response to

Access All Areas

Tony Heaton

And that glittering prize was coughed up, again and again Northern boys, drumming, running, breathing rhythms, insistent,

Stopping ...

My dead father in that short silence

reaches into my memory to light another fag

Spitting mad, Bobby's little bobbles, puckering,

chuckling, spitting images

Jenny nipples, weighed, Bobby nipples mustard relish, Noemi nipples,

chapel hat pegs in the school chapel, trembling ... undressed to the sound of a 2001 space oddity and the smell of fresh paint

— life repeating life —

we are all voyeurs here

Pete dances to the fart-powered horn

the bumper legend was Saxo

and this car auction lot towered into a pillar of salt

salt chicken, chicken wire, chicken feather, chicken shit silver figure, moving silver cross prams by powered wheels onto the buses we were chained to without power,

but waving banners

Bobby banners on the river

Daylight, brings the 'seizure' of the 'brave' word

control and power through fear

the blue-badge that celebrates the Noble erection

before a handi-black-cap to contain

The hypo-crip-tic sick messages

elegant muscles with minds of their own as we are submerged by water and words

into thinking all property is theft ...

and Jon's flags fly high and dry with

... no strings, of words, attached

[On my reciting of the last line, Jon Adams throws his cut-out written words up into the air like confetti towards the audience]

Lois Keiden:

Access all Areas Live Art and Disability

Access All Areas is a combination of artists’ writings, creative dialogues, critical commentaries and DVDs featuring documentation of artists’ presentations and performances spanning 20 years, which reflect the ways in which Live Art has represented issues of disability in inventive and radical ways. This 200 page publication and double DVD set has been developed from the groundbreaking Access All Areas public programme of performances, screenings and talks produced by the Agency in March 2011.

Featured artists and writers include Jon Adams, Katherine Araniello, Ron Athey, Back to Back Theatre, Bobby Baker, Caroline Bowditch and

Luke Pell, sean burn, The Disabled Avant-Garde, Pete Edwards, Extant, Mat Fraser, 15mm Films, Lyn Gardner, Girl Jonah, Tony Heaton, Raimund Hoghe, David Hoyle, Noëmi Lakmaier, Brian Lobel, Catherine Long, Rita Marcalo, Alan McLean and Tony Mustoe, Kim Noble, Martin O’Brien, Sinead O’Donnell, Maria Oshodi, Mary Paterson, Áine Phillips, Juliet Robson, Sheree Rose, Rajni Shah and Aaron Williamson.

‘Live Art is truly the avant-garde forum for Disability Art and at the forefront of Disability Art practice, thinking and theory.’ -- Dr Paul Darke, 2011

“…a publication that encapsulates the wealth of creative talent beavering away within the Disability Arts scene, contains the very best of their work, intelligent comment and discussion of process and practise, and looks great too. I believe it will become a seminal publication, not only for the Disability Arts world which it exposes beautifully but for the wider arts community as it demonstrates how make art books accessible. A must have for anyone interested in the arts and creative practice.”

A-N Interface, 2014

Royal College of Physicians, Reframing Disability Representation

`Good access to buildings ... public transport systems, accessible information, decent and appropriate services, education that meets our needs — removing' the barriers to these "taken for granted" things will often be cure enough.'

Thinking about difference ...

What's the difference between God and a doctor? God doesn't think he's a doctor.

It's a very old joke, but it always seems to surface in my consciousness when disability and the medical profession are mentioned in the same sentence. The relationship between disability and medicine is often contentious, and many disabled people are critical of the power the medical profession has over their lives.

Anecdotal stories abound. These are tempered by the huge impact that medicine and the medical profession has over all our lives. Many of us, including me, would not be alive without this intervention, yet others are impaired by it — a paradox of major proportions.

For those whose lives are untouched by disability and the barriers faced by disabled people, their families and associates, and who have little contact with the medical profession, there might be an assumption that our lives are inextricably linked to physicians, but for many disabled people this is simply not true.

`Shape has been and remains a pioneering organisation, which, for the last 30 years, has worked with a plethora of organisations within the cultural sector, including the Royal Opera House, British Museum, the Tate and the National Theatre, training staff and advising on access.'

become a clash of ideologies? Would the images be medicalised? Would disabled people simply be seen as objects of scrutiny, gazed at through the microscope, labelled, named like some botanical specimen, defined in Latin?

Well of course we should be involved. Shape is a disability-led arts organisation working to improve access to culture for disabled people, if we are not prepared to enter into problematical areas or dialogue with unlikely partners, then what are we for? Shape has been and remains a pioneering organisation, which, for the last 30 years, has worked with a plethora of organisations within the cultural sector, including the Royal Opera House, British Museum, the Tate and the National Theatre, training staff and advising on access. We undertake a wide range of projects with a huge variety

of partners and across all genres. In this instance we were fortunate to have Bridget Telfer as our connection to the RCP — she was open, honest, genuine and wanted to learn.

The proposition was stunningly simple: images of historical disabled people existed in the RCP collection, little was known about them, it would be interesting to commission some research and find out more about the lives and characters behind the images, and then to see the individuals within a wider historical framework, to get some sense of how disability was considered at that time. Following this research, disabled people involved in the arts and cultural sector would be invited to come together in a series of focus

groups to have an open dialogue about the images and the research, and we won't see what would unfold.

Shape's role was to advise on the planning of the focus groups, to host and facilitate them and also provide disability equality training for all project partners. Shape also attracted disabled participants to the project through our newsletter and through follow-up discussions with interested parties to explain how the process would unfold. We also worked closely with Bridget and her team to formula the content of the workshops. The RCP commissioned the academic input and research from Julie Anderson and Carol Reeves, who had knowledge and expertise in both disability and medicine, coup with a great sense of humour.

Seeing the historical images for the first time was a revelation. Unexpectedly, most were images of people who did seem to have a degree of control over their lives, marketing their difference and capitalising from it. The majority were pre industrial revolution, the onset of the industrial revolution often being described as the time in history where the 'care and control' of disabled people began. Marginalised through mechanisation and standardisation, disabled people became 'misfits'. Yet the people in a number of these images were not subjected to that oppression; they had created a condition where they exploited their difference and controlled their own destiny.

This combination of people and subject set us up for a thought-provoking three ays- 6f focus group and created sufficient material for the subsequent exhibition. It was an interesting partnership, and the work and commentary of the contemporary participants should speak for itself. And the voices c the long-past disabled people captured within these images, what of them? Well, much is conjecture( For me, the need to properly document our lives as disabled people, and to have this set within a contemporary context remains paramount. The need for a National Disability Arts Collection and Archive remains pressing, and the materials gathered from this venture between the RCP and Shape should become another important link in this largely hidden chain.

Edited by Bridget Telfer, Emma Shepley and Carole Reeves

Re-framing disability explores a group of rare portraits from the 17th to the 19th centuries held by the Royal College of Physicians. The portraits depict disabled men and women of all ages and from all walks of life, many of whom earned a living exhibiting themselves to the public.

Critical to the success of the project was the involvement of 27 disabled participants from accross the UK, who came together to

discuss the historical portraits and their relevance to their lives. Participants were also invited to have their photographic portraits taken, and to be filmed.

The catalogue reveals the story behind the creation of the Re-framing disability project, the research findings exploring the historical portraits, and the autobiographical text of the disabled participants.

Contents

• Preface - Emma Shepley, curator and heritage manager, Royal College of Physicians

• Medical or social? A note on models of disability - Julie Anderson, senior lecturer in the history of modern

medicine, University of Kent

• Realising 'Re-framing disability' - Bridget Telfer, project curator, Royal College of Physicians

• Thinking about difference... - Tony Heaton, chief executive of Shape

• Public bodies: disability on display - Julie Anderson

• Historical portraits of disabled people at the Royal College of Physicians - Carole Reeves, outreach historian,

Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine, University College London; Julie Anderson and Bridget Telfer

• Contemporary photographic portraits and autobiographies of disabled participants

• References

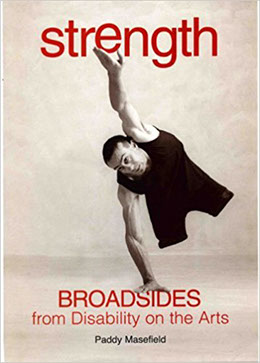

Paddy Masefield: Strength, broadsides from disability on the arts

WHITE ON WHITE

Barbara, Johnny and the Quiet Revolution (2001)

Tony Heaton

(ICON OF A DECADE #15)

(mixed media)

This piece 'concerns language: the language of art and BSL (British Sign

Language). Next to English, the language I use and need most, but not

offered as part of my compulsory state education that forced oral and

European options only'.

I accepted the invitation to join the Board of Coventry's Bel-grade Theatre partly because it had a large and easily acces¬sible box at the

back of the auditorium, which enabled me to sit with other wheelchair friends, close to the accessible toilet and ramps to the bars. My one proviso was that I should be able to reach their excellent restaurant without having to go through all three courses of the kitchen flooring.More purposefully, I suggested to the TMA that they might like to be proactive in the creation of a national and permanent British Deaf Theatre. The message this could send out to the eight million people who self-define as hearing impaired might be more audible than eight million posters to unsigned perfor-mances. Assuming they wanted to maintain their centuries-old tradition of theatre being a voice for the common man — and more recently woman — and a fun palace for young people, that voice would be expressed through British Sign Language (BSL).

Tony Heaton entitled the picture opposite White on White, thus playing with the ambiguity of the titles to many modernist works of art. But its subtitle: Barbara, Johnny and the Quiet Revolution told a more melodramatic tale. Johnny Crescendo and his partner, stage-named Wanda Barbara, were the main acts for a Disability Arts Cabaret at a 'special' school. Johnny has a rock and roller's predilection for not just volume but raw language. The non-disabled organiser's taste was for censor¬ship. So he simply pulled the plug on the amplifier.

In response to the paternalistic way many people in institu-tionalised settings are treated, Johnny and Barbara circulate: a poem. Its message was that disabled people were allowed t: say thank you to mainstream performers who entertained them with their charity, but were not allowed to express contrary view. Each verse concluding 'but they do'! Tony reference to a 'Quiet Revolution' was that only in 2003 has sio-language been recognised as an official language! In this a—. work the top line of arts conservators' white gloves spe `smile'. But to read the bottom line you will need to find a BS _ user.

This remarkable book is the first to focus on disability arts. Drawn from over 50 of the author's speeches, it offers readers the excitement and diversity of Disability Arts and the artistic expression of formerly excluded sectors of society, such as people with learning disabilities and survivors of the mental health system. It is concerned not with their medical impairments but with the insight and originality of their art works that are beginning to fill a space on the canvas of arts history that has too long been blank. "Strength" is intended for disabled and non-disabled people, arts professionals, teachers and students of the arts, sociology and humanities, from school to university level.

Mary Dejevsky, columnist in The Independent - 2012

Tony Heaton reflects on how far we have come to make arts buildings accessible to all.

See the article HERE

Thoughts from a Train…

Small children and cultural leaders perhaps share two things in common: a sense of wonder for the world and the ability to constantly ask the question, ‘Why?’

For cultural leaders, this sense of wonder can be translated into how we might harness innovation into our organisations to make them better. We should ask the question ‘Why?’ to anyone and everyone who is kind enough to tell us anything about the performance of our organisation: our service; how we do things; and how we might do things better.

To do this, leaders need to have their heads above the desk. I am often asked what I do and I often say, ‘As little as possible’. It’s a tongue-in-cheek response, but if leaders are too immersed in the day-to-day minutiae of their organisation, then they will not see it within the wider context. I have held onto a quotation but lost grip of where it came from, but it is something like: ‘See distant things as if they are close and close things from a distance.’ For me, this translates into having a very clear vision of where you want your organisation to be, how it will look and what and who you will need to take you there. Painting this vision to everyone, constantly, will help to make it real, even though that future may be distant. The people you talk to are the people who will help you realise the vision. Close day-to-day challenges often benefit from a distant, objective and cool approach rather than knee-jerk solutions; this sometimes takes courage, particularly if those around you are clamouring for action.

I think some leaders are formed and some are natural leaders. Traits of leadership can be acquired and leadership does not have to be a constant; different people in most dynamic organisations will take on a leadership role at some point. One of my favourite analogies is when birds fly in ‘V’ formation, there is clearly a bird at the front but the leadership changes throughout the journey, as each bird has a special relationship pattern to the birds in its proximity. This results in the emergence of harmonious self-organising patterns. I believe that it is important for this also to happen in organisations.

As an obviously disabled person – I am a wheelchair user – I see, almost daily, looks of disbelief or surprise when people realise I lead an organisation, even though I have successfully led organisations for over 12 years and have chaired organisations for longer. Many of the disabled people I know are creative, flexible and lateral problem solvers, resilient, constantly responding to change, consistently challenging low expectations – they have to be, just to get through life. For instance, getting out of bed in the morning may have needed the organising and managing of a ‘personal assistance’ team and meeting the challenges of so-called ‘public’ transport and the general inaccessibility of the built environment requires real tenacity.

However, there is still prejudice and a reluctance, particularly among the larger disability organisations (never mind the mainstream), to employ disabled people to lead organisations, even though these very organisations should be best placed to offer leadership training, mentoring, advice and guidance. These organisations have not learned from discrimination and have done disabled people a great disservice in reinforcing the negative stereotypes that many people hold about disabled people. Is this because these organisations only promote people like themselves and cannot see disabled people beyond the recipients of the care and control tactics they perpetuate within their organisations? If true, I would argue that this is because often we promote the wrong type of leaders.

Some leaders are picked because they are very good at what they do within the organisation; they are plucked from their productivity on the ‘shop floor’ and become management fodder. This approach can lead to both a loss of productivity and the creation of yet another bad or ineffective manager.

Leaders should appear to do very little and delegate ruthlessly; they should listen, think and spend time dreaming about their organisations. Plato considered contemplation to be the highest form of human activity, the aim of life being to see life rightly, not to change the world. In our ‘busy’ age we should constantly question what we are busy doing.

So, what is it that makes our organisations good, or with the potential to be great? What are the leadership qualities required; who are the people who are pulling the organisation into the future, rather than being pushed by the past; and how do we part company with those that hold us back? Good leaders need to surround themselves with the best possible team. I have worked with good teams and with no team, and I know which I prefer. Building the team takes great skill and discernment; an understanding of people’s preferred learning styles; and perhaps more importantly, making sure they understand yours. If they don’t, you are likely to face real problems which will distract you from your purpose.

Some of the most useful and insightful observations I have benefited from come from volunteers or those on the edge of an organisation. Perhaps this is because they have not ‘bought into’ the corporate view, are not immersed in the organisation and can see more clearly? Good leaders share as much as possible: by sharing, we sell the vision and encourage a response. Those on the edge of the organisation may be more candid in their view than those within the organisational hierarchy and, while they may not always tell you what you want to hear, it’s vital to listen to their response.

If I were to define my own road to leadership, it would be one of entrepreneurial and evolutionary development. It was unplanned and I

would assert that most of us cannot remember why we took most of the important decisions in our lives that we did.

I was already termed a so-called leader long before I had any specific leadership training. When I did, it was a revelation of sorts. Back in 2001, the Association for Chief Executives of Voluntary Organisations (ACEVO) promoted a course on process work, entitled Leadership in the 21st Century, facilitated by Dr Max Schupbach. When I arrived at the training room, there was not a flip chart in sight. We sat in a circle waiting for the leader to begin. We kept waiting until someone asked when we would start. After a few seconds thought, Max said we had already started. He then talked a little about the self-organising tendency. More silence. Some people started to complain and said they had paid to come to learn about leadership; someone else said that was precisely what was happening – we were learning about leadership through the process of seeing what would unfold, who would come forward to lead. It was amazing how angry some people became. They felt cheated, but it was a revelation to me about predetermined expectation and institutional thinking. Some people left – I like to think to go back to those large disability charities they were leading...

We talked about unconscious rank and why most white, non-disabled, middle class men walk into a room that is full of people like them without even noticing it. This was interesting to me, the only disabled person in the room who was talking with the only Black person in the room. In many ways, the notion of process work is not about rules of behaviour but about relationships, as the individuals, the community and the organisation change and flow throughout the journey.

I used the word evolutionary above, because some of the things we talked about were comfortingly familiar and I was doing them, I just didn’t know the management speak to define them. The same with entrepreneurial, because I have always had my way of doing things, constantly looking to do deals and maximise advantages. You can’t do this with your head down on your desk. I was always confident to succeed; I don’t know if this was arrogance, perhaps, which prompted the need to work on humility and kindness, but I think having confidence gives confidence. This is particularly important in relationships with funders, who have to be sure they are getting great results and best value for money, and also to those who will be helping to realise the vision you are painting.

I think perhaps that in the creative and cultural sector, in looking inwards we take creative thinking for granted. If we do, then this is a mistake; it is one of our most important assets on which we need to capitalise.

As an artist, I am encouraged to experiment, discard ideas and take risks; this is not considered as failure. As such, I think it is important for our sector to be more open to failure; to fail better; to embrace thinking differently; to be counter-intuitive; and to take these approaches out to others as an asset. Collaborations with others outside of the sector could be fertile ground: artists on the boards of banks and financial institutions; artists as school governors; artists in those places where there is institutional thinking; artists infiltrating places that might be hostile. My daughter is a school teacher and showed some of my work in an art class. At the end, a child asked if she was sad because her dad was dead. My daughter explained that I was very much alive, but I wonder how many other young children think of artists as people from a long dead historical past rather than leaders shaping the future.

Ezra Pound (1954) described artists as the antenna of the race. As such, artist-leaders should be aware and free to think, explore, fail, test and push boundaries. This is increasingly difficult in a world that becomes more and more regulated by a tick box mentality, where decision-makers are terrified to make decisions because of fear of failure, and a new prurience and hypocrisy strangle honest debate.

To achieve this would need real discernment and some bravery from funders, and openness from their institutions, but if the creative and cultural sector only has a dialogue with itself, then our value will be very limited and will atrophy. The McMaster review (2008) considered how public sector support for the arts can encourage excellence, risk taking and innovation, but I must have missed the pots of money available and the present climate makes people more risk averse. All the greatest discoveries and journeys have been laden with risk. We need to look outward to new opportunities and engage with those outside the sector, in talk away from ‘art-speak’.

This vision thing, and the idea of leadership, reminds me of something Picasso is reputed to have said, that in essence he had spent his whole lifetime learning to paint like a child. This takes me back to the starting point of this reflection. Being open; constantly asking the question ‘Why?’; listening; discerning through all the monkey chatter and busyness what is right for your organisation; and, with the combination of experience and vision, successfully painting that vision to others – it is then that the direction becomes clearer.

I thought I would finish with a quotation from Hans Moravec, a pioneer in robotics, who talks of the future, or perhaps even the present. It comes from John Gray’s provocative book, Straw Dogs (2002). Moravec said, ‘Almost all humans work to amuse other humans.’

This may come as a great relief to all in the sector.

I wrote this on the night train between Florence and Paris, one of the advantages of not flying, even in ‘V’ formation.

Shape Arts

Lulu Nunn and Tony Heaton in conversation

Tony Heaton OBE is an artist, long-term disability rights activist, key figure in the Disability Arts Movement, and outgoing Chief Executive (soon-to-be Chair) of disability-led arts organisation Shape Arts. Lulu Nunn works at Shape on programming, audiences, and marketing, and is also a curator and writer.

Lulu Nunn When people are new to Shape, I guess the first thing we always introduce them to—whether they're artists, our staff, other organisations; disabled or not—is the Social Model of Disability, which informs everything we do. The Social Model is a triumph of discourse in its own right, and serves to open up the way we think and talk about disability and ableism no end; in having being developed by disabled people in the 1970s to give them the ability to discuss their own lives, and the power of discourse on their own terms. Language and discourse can both give and take away agency from people—in private, social, cultural, and political respects.

Tony Heaton A friend had her foot and part of her lower leg amputated and was incensed when the doctors and physiotherapists kept referring to her 'stump', for example 'rest your stump on this pillow'. They emphasised the medicalisation of the situation; she maintained it was still her leg and wanted to retain the term `leg'—her term and her agency, because it was still her leg and it was the leg that was the issue. This is why language has always been a key issue for Shape, and plays such a big part in our Disability Equality Training, which we offer to arts organisations and cultural institutions who want to become accessible and inclusive of disabled people—that's definitely a huge way in which we've been instrumental in actively shaping (some pun intended) discourse around ableism within, and reaching out through, the arts.

LN Shape's now 40 years old, so it's been there throughout the Disability Arts Movement, which was so instrumental in gaining rights for disabled people, hand-in-hand with the artists (including you Tony) who were on the front line. The organisation was and still is a firm player in terms of disability rights and artist-led discourse around ableism and disability, and it's a history we build on every single day. The Guerrilla Girls put it so well when they said that 'unless all the voices of our culture are in the history of art, it's not really a history of art—it's a history of power'. The Disability Arts Movement is such an important heritage story, both in a 'lest we forget' way, but also in that it shows that we can absolutely keep achieving human rights through creating and sharing discourse-based artworks.

TH Well this is why NDACA (the National Disability Arts Collection and Archive, a major project delivered by Shape) is so vital! It presents the Disability Arts Movement in the context of the recent past and how it has shaped today. When we open the NDACA wing at Bucks University next year, it'll also provide a physical space for research

and study, which will enable so much discourse around disability art, rights, and ableism. Research and study can enable a discourse with the past.

LN From the past to the future—our youth forum has also served an important purpose in giving young disabled people the language, tools, knowledge, and resources to have their own dialogues around disability and access, and to drive their own futures within the creative industries on their terms and in a way that upholds their rights. Shape has been creating physical spaces for people to confront and talk about disability and ableism since its inception—our annual Open exhibition, for example, is quite literally intended to be a space which fosters discourse—'where disabled and non-disabled artists can discuss and exchange views and ideas about issues and topics [around disability] which are often sidelined within artistic debate'.

TH Everything we do does this, sometimes it's more subtle and subversive but I think if you interrogate what we do you will find that it is all there to create a dialogue and challenge ableism: the exhibitions, the putting together of disabled and non-disabled artists, NDACA and the owning of our history, putting disabled artists in contemporary galleries as Bursary recipients, giving Disability Equality Training, access auditing, partnering with other organisations, working with Arts Council England and the government to try to highlight the lack of diversity, the empowerment of young disabled people...

LN I've always thought the arts auditing and training service we provide are really important in that it gives other organisations in the art world the tools and knowledge to actually open up to disabled people as workers, creative, and audiences, and stop marginalising them. So many museums and galleries and theatres play host to really ground-breaking, political, socially-engaged work, but fail when it comes to actually physically opening up to disabled people, and in doing so don't provide a platform for disability-led discourse. It's very disempowering and difficult for an individual to challenge. Johanna Hedva, who writes so eloquently and brilliantly on the body as a commodity under capitalism, and (I'm hugely paraphrasing) capitalism's trap of the necessity to physically fight for your rights as a sick or disabled person—'how do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can't get out of bed?'—illustrates so perfectly the power of discourse via creativity in the struggle for rights. The power of words, not deeds.

Images opposite

1 Noemi Lakmaier's Cherophobia (2016) performance was one of the most recent Unlimited commissions. Unlimited is the arts commissioning programme for disabled artists which Shape Arts co-run with Artsadmin.

2 Aaron Williamson's Demonstrating the World (2016) was another of the most recent Unlimited commissions.

3 Installation image from Simon Raven's three-month residency at Camden Arts Centre. Raven was the

2012 Adam Reynolds Memorial Bursary recipient.

4 The Shape Open 2013 winners and panel. From left to right, artist Katherine Araniello, Bow Arts CEO Marcel Baetigg, artist Eric Fong, Shape Open patron Yinka Shonibare MBE, Shape Chief Executive Tony Heaton OBE.

5 Justin Piccirilli's piece Stone of stumbling, rock of offence won the 'people's choice' in the 2016 Shape Open.

6 The photographer Mark Tamer (right) in residence at Shape's pop-up gallery in Stratford, assisted by Shape Youth Leader Revell Dixon (left).

Access and representation shouldn't have to be luxuries for marginalised people; the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that, 'everyone has the right to freely participate in the cultural life of the community [and] to enjoy the arts'. It's all about power and rank really, and very few disabled people have either. Shape has always been focussed on protecting the gains made by disabled people and expanding these gains through the arts—it's cliche but true, art really does transcend boundaries, communicate ideas, and create empathy. Disabled people are not heard, and certainly not actually listened to, by non-disabled people. Art challenges how we're seen as insignificant, not compos mentis, undeserving of real choices when it comes to our lives, or just unlikely to have anything relevant or important to say.

LN I think that's really important given that, at the moment, it seems like there's a growing trend against what's seen as 'political correctness': not oppressing people is increasingly seen as either radical or fragile, but fundamental human rights shouldn't still have to be a radical notion. Shape celebrates social justice—that's valuable. Once we can illustrate to artists, curators, programmers, gallerists, and those who are running the museums, the art schools, the magazines and the like, through our own work with and the promotion of disabled artists, that their inherent ableist prejudices are unfounded and damaging, that's when we can start showing them how to actually become accessible; how to stop gatekeeping and withholding what should be available to everyone, how to empower disabled people. Knowledge is power, but if you are prevented from accessing knowledge, then access becomes power.

TH Disabled people have always had gatekeepers, such as the medical profession and social 'care' practitioners—those who control the institutions and the experiments. So-called 'special' schools had little to do with education and were much more about care and control, and the very use of the word 'special' in this setting is hugely open to question—it's a very comforting word and I am sure those outside of the system imagined young disabled people having all their needs met, but this is not the case when you talk to many of those who went through the system. Dr Paul Darke always illustrates this well. He said that, 'I went to a special school which chose not to educate us.

It was for kids with spina bifida. They probably thought we'd end up in a home or die'. Disability rights activist Baroness Campbell also talks about this—when she has to go into hospital her husband brings all the photographs of her being inaugurated into the House of Lords to

emphasise that hers is a life worth living to the hospital staff, who may well see death as the 'kindest' option. Perhaps this is also why so many of our artists work in self portraiture—to enable themselves to be seen by an audience as they see themselves and wish to be seen. The whole debate around 'assisted' dying is exposed through the important work of disabled artists such as Katherine Araniello and, recently, Liz Carr's phenomenal 'Assisted Suicide: The Musical' (2016), was based on an assumption that our lives are somehow less and not worth living. These artworks create dialogues that alter public

Knowledge is power, but if you are prevented from accessing knowledge, then access becomes power.

perception to remove some of the prejudicial barriers that disabled people face; this is one of the key reasons that we funded and supported 'Assisted Suicide: The Musical' through the Unlimited programme we co-run with Artsadmin.

LN I didn't fully grasp this side of the euthanasia debate until very recently—until I saw ASTM, actually—and realised that even the perspectives I'd experienced of the people who wished to be helped to die had largely been washed into them by an ableist society. They were the perspectives of people who had become sick or disabled late in life rather than those who had lived—who are living, I should say—their whole lives as such, and were lamenting the loss of their former lifestyles and their descent into the 'undesirable'. I sent the amazing art critic duo The White Pube to see ASTM and they subsequently wrote about it as thus, 'the politic is this: assisted suicide is seen as a way to fix the problems of both disability and terminal illness—painted with the same brush. "It's better to be dead than disabled," better to be dead than facing a terminal illness, because of the loss of autonomy. (Pain is much lower on the list for cited reasons for assisted suicide, I didn't know this). Thus, assisted suicide is a threat to disabled people, to their day to day, their value, their identity.' The understanding and empathy that comes out of the discourse generated by the work we support and enable—that's astonishing; it's what Shape has set out to achieve, and it's what we can keep achieving.